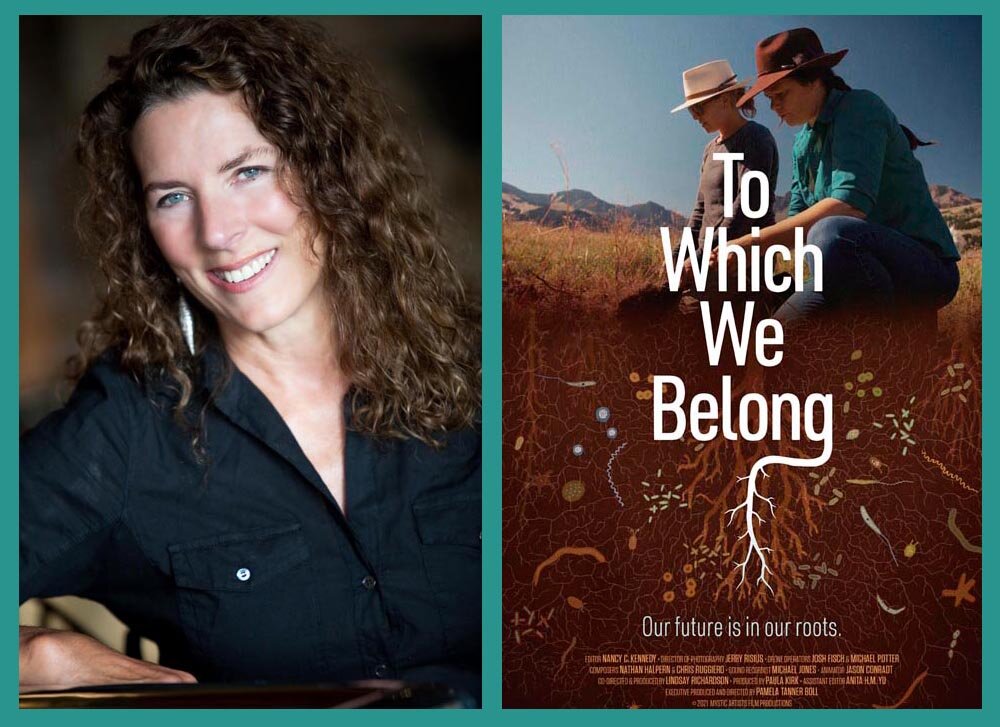

Pamela Tanner Boll, Director of ‘To Which We Belong’

By Susan Messer

“To Which We Belong” is a documentary that highlights farmers and ranchers who leave behind conventional agricultural practices that are no longer profitable or sustainable. These unsung heroes are improving the health of our soil and sea to save their livelihoods—and our planet.

This film will screen at 3 p.m. CDT on Sunday, April 25. Tickets available to U.S. viewers only. After the movie, stay connected so you can participate in a conversation led by Susan Lucci, Soulful Facilitator and Purpose Guide; Co-Founder, Global Purpose Guides and FeelReal. She’ll talk to

Lucia Leon, Farm Manager, Herban Produce

Anton Seals, Jr., Executive Director, Grow Greater Englewood

Susan Messer interviewed Pamela Tanner Boll, director of “To Which We Belong.”

Q: How did you focus in on this particular topic?

A: I’m a big reader, and about 5 years ago, I came across two books that got me going. The Soil Will Save Us, by Kristin Ohlson, and Cows Save the Planet, by Judith Schwartz. They introduced me to the idea that without cows, our grasslands die, that the grasses need to be eaten down—not too much but just the right amount. And when they are eaten down, their roots grow deeper, which sequesters more carbon in the soil and helps with moisture retention. This was all very interesting to me, as I’d been hearing so much about cows and beef being bad for our planet. Also I saw a TED talk by Allan Savory, a Zimbabwean ecologist whose ideas are controversial because he says that we’re doing a disservice by asserting that farmers shouldn’t have cattle. Cattle are essential when they’re allowed to roam. Their roaming, combined with more plant diversity and the elimination of pesticides and herbicides, improves soil health as well as the nutritional value of the crops.

Alejandro Carrillo at Las Damas Ranch, Chihuahua, Mexico.

Some farmers have begun to see that their traditional farming practices are actually killing the soil and its useful microorganisms. They’re seeing that when the soil is healthy, their plants can withstand the pests. As I learned more about all of this, I wanted to know more. I wanted to see whether these ideas and practices—referred to as regenerative agriculture—could spread further. And thus came the film.

I am not a scientist, but I am a very curious person. And I’m scared by the enormity of climate change, so I’m interested in new ideas. Improving the soil with the methods featured in the film is the most impactful, most immediate thing we can do to address global climate change.

Q: Tell me about the film’s title.

A: It comes from a quote by Aldo Leopold (1887-1948)—a revered environmentalist of the past century. He said, "We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect." In other words, land is something we can’t live without. Humans don’t live in a vacuum. We depend as much on the health of the ants and the bees and the dung beetles and the soil as we do on the larger flora and fauna.

Q: How did you find the stories and people you wanted to present in the film?

A: Through a variety of networks. I went to a conference sponsored by the Quivira Coalition, an organization whose mission is to build soil, biodiversity, and resilience on western working landscapes. This organization brought ranchers and environmentalists together to find common ground. I also contacted the Savory Institute, which is dedicated to building grasslands around the world and teaching about holistic farming practices. The Nature Conservancy was another source; they have been very active in working with farmers both here and in Africa to help them move toward regenerative practices. Along the way, I found a guy who is doing ocean farming, growing kelp, which absorbs carbon like you wouldn’t believe. Then he incorporates the kelp into cattle feed, which is both very nutritious and very digestible, keeping the cattle from emitting those nasty gasses we hear so much about.

A field of rye at Harborview Farms, Rock Hall, Maryland.

An important thing for people to know is that this film isn’t just about farming in the U.S. or in one kind of ecosystem. One of our stories takes place in the Chihuahuan desert of Mexico; another focuses on traditional cattle herders in Kenya. We also went to the middle of Nebraska, to the Atlantic Ocean off New England, to Paradise Valley in Montana. We wanted to show that no matter where you are, the principles of regenerative agriculture apply.

Q: A troubling feature of today’s world is the us vs. them mentality--for example, ranchers vs. environmentalists, fossil fuels vs. renewables. Do those kinds of issues surface in your film?

A: One distributor especially liked the film because it doesn’t go down the road of good guys vs. bad guys or red state vs. blue state or wildlife vs. cattle. But a lot of people like stories that have good and bad guys; those stories are more dramatic, so it’s hard for filmmakers to avoid the temptation. Still, my thinking is that, for example, fossil fuels have a place, but we also have to explore alternatives. Cows aren’t bad; it’s how they’re grazed; they need to be herded from pasture to pasture.

I like to explore the places where people with very different ideas come together. For example, in the film we have a big, multi-generational family of farmers from Nebraska. It’s a very conservative part of the country, and these farmers were raised to manage their land in the old, conventional ways, but in the 1980s, for a variety of reasons, they started exploring regenerative agriculture, and . . . well, come see the film to find out.

Q: What surprised you in the making of this film—about anything, people, issues, challenges?

A: People have a hard time changing their minds about anything. Changing the way they work, the way they’ve always done things, involves a lot of uncertainty. But what I learned in the making of the film was how central love was in these people’s willingness to change. Of course, concerns about profits and costs and, sometimes, illness played a role. But at bottom, the adaptations you see people make in this film came out of care and love for their family, friends, animals, legacy. These stories have a lot of heart.